III.

Thoughtful preparations were central to Paleoindian life. It was commonly observed that all things possessed transcendent consciousness, or spirit. Animals, plants, rivers, mountains, and people alike had their own unique intentions and could thus be influenced. In this context, the relationships between all things existed without doubt or contention. In this regard obligations of respect that were not properly paid to the spirits of prey could jeopardize the yield of a hunt, or the prospects of future hunting. Each stage of preparation from creating tools, to stalking, killing, processing, distribution, and disposal had its own unique rituals and taboos designed to appease the spirits.

Success of the hunt was of paramount importance as it meant survival of the group. The stakes were high as the possibility of insufficient food supply was always looming. The late season hunts were especially meaningful as their bounty would allow for stockpiling of supplies required for the inevitable long winter ahead. In addition to meat, the animals caught would be harvested for materials to produce clothing, blankets, rope, tools, and crafts for trade. No part of the animal was wasted.

Paleoindian groups like Ni’s were efficient hunters. Men and women alike would participate in the process and would hone their skills throughout their lives. From the time of childhood, they would learn the behavior of the local animals and their ever-changing landscape. They would create and carry a variety of stone tools that would be used for butchering and animal hide processing. These tools included fluted spear points, and various types of micro-blades. They would also produce stone axes and chisels for other common uses. These items were often transported with them as they traveled. Alternatively, seasonal use items like fishing hooks, traps, and spears would be hidden in strategic caches near established camps and hunting grounds. When clans gathered at large communal sites like Siwaba, it allowed for such tools and source materials to be compared and traded among the groups. It also provided a time and place for engineering methods to be shared and existing the technology improved upon.

The stone, wood, and bone used to create their tools could come from hundreds of miles away. Some of the finest lithic materials (fine grained rocks such as chert, rhyolite, and argillite) were procured from far West and Northern quarry locations. The location of these distant quarries was guarded information only known to certain groups or individuals.

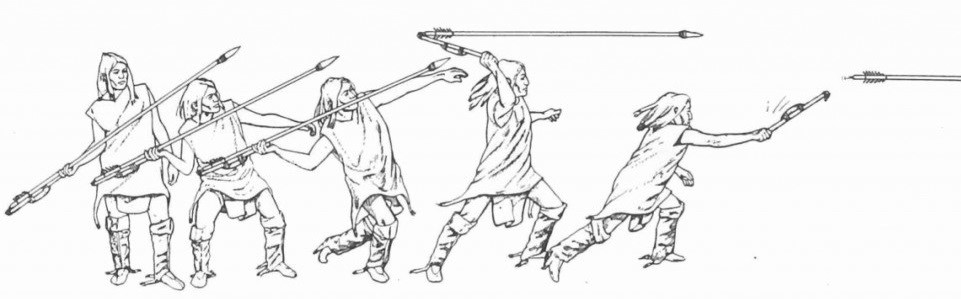

As they became men, Awaas and Mateg developed into well respected contributors to the hunt and its rituals. Mateg, the elder, was known for his high-quality precision stonework. In earlier years he had been granted knowledge of, and visited the quarries located in the distant Northern mountains. His signature creation was a large fluted projectile point that he would mount on a spear, or dart. It would be fastened to straight but flexible wooden sticks. These projectiles could be thrown by hand at a target. Smaller versions could be propelled by atlatls. Like bows, atlatls could pitch flexible pointed shafts — called darts, at high speeds across long distances. Atlatls were essentially wooden sticks that contained a hook or spur at one end. This notch would hold the dart or spear. By swinging the atlatl overhead and forward, the hunters could launch their darts with greater force than if they were to throw them like javelins.

The projectiles created by Mateg and his contemporaries were built to withstand the shock of penetrating thick animal hides and with the intention to produce lethal wounds. To satisfy their need for meat protein, they hunted a variety of animals including caribou, deer, elk, beaver, and fox as well as smaller animals including birds, rabbits, fish, and seals. Beyond the use of spears or darts, they also utilized elaborate traps for small animals, and bone hooks for fishing. They also relied on the bounty of local shellfish available during the summer.

As Mateg was known for his stonework, the younger Awaas was appreciated for his keen ability to stalk and ultimately kill larger game. Awaas physically appeared different then his more compact peers. He was taller, more muscular than most. He possessed incredible physical endurance and speed. He was known to have tremendous hand-eye coordination and could hit a stationary target with his spear from great distance. For this compelling reason, he often was looked upon by the clan to guide them in physical ventures like hunting or building.

During the annual late summer full moon, the brothers would lead the men and women of Siwaba on a large-scale caribou hunt. Pre-hunt rituals included several days dedicated to production and maintenance of the tools and connecting to the animal spirits. Multiple groups, mixed of elders and young, would set up around the central fire diligently working on their spears and flint knapping. In this act of group preparation, the hunting party would forge its strongest bonds. Ultimately these bonds would ensure cooperation and steadfast focus among all during the impending harvest.

For generations it had been observed that the large caribou would travel in herds and migrate south along the coastal plain during the spring and summer months and would concentrate, breed, and forage on near-shore islands that had adequate vegetation to support them. One of the most bountiful of these islands was accessible via a short hike from Siwaba.

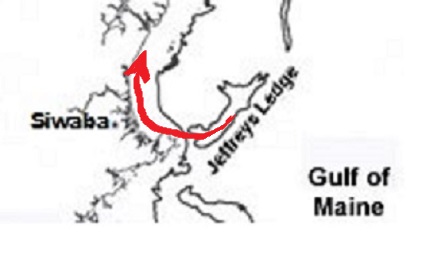

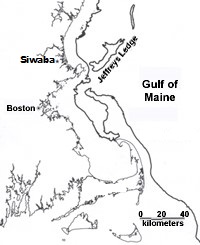

In their time (~8500BCE), the sea level within the Gulf of Maine was approximately 180 feet below its present height. The ancient geographic landscape appreciated 10,000 years ago exposed a substantial area of land that now lays quietly submerged 150 feet below the Gulf of Maine. The modern hallowed fishing grounds known as Jeffrey’s Ledge would have been appreciated as a substantial Atlantic island at the time. It was separated from the mainland on its southern end by a mere 1.5-mile-wide channel. They called this island Libo.

Libo was a large and narrow offshore island that was located due East of Siwaba. Libo and the near shore landscape provided an ideal environment for the caribou’s annual retreat. After a summer of grazing on the island, the caribou would be well fed, and their coats would be in excellent condition for harvest. Given its unique geography, the island would serve as a bottleneck for the large game as they returned to the mainland.

Swimming Westward across the 1.5-mile channel to dry land, the herds would ultimately emerge from the water and begin their annual Northern migration following the edge of the coastal plain. It was not long before the herds would pass directly off the eastern point of the Siwaba encampment.

As the caribou emerged from the water their instincts would lead them toward the cover provided by the hills and woods on the western aspect of the plain. Mateg, Awaas, and their contemporaries were aware of the animals’ behavior, and would take full advantage of this knowledge. Strategically they would spread out East to West across the coastal plain at metered intervals in a human line. Between them, they would also set intermittent large narrow rocks or logs upright. These structures would be adorned with human hair and animals hides to trick the caribou into sensing the presence of more people. The use of these “dummies” would be especially practical in years when the number of hunters was low.

As the caribou herds made landfall the hunters would make lots of noise and motion to startle the large beasts. The caribou herds would sense the danger and out of fear, would be naturally be driven toward the local encampments. As the topography surrounding Siwaba provided a natural game drive system, it allowed the hunters to direct the traveling caribou very efficiently. When the moving herds approached Siwaba’ s Northern edge, more community members would be waiting to direct them into the funnel shaped valley that ran along the western edge of the land mass. Upon entering the valley, the hunters would close in on the herd from behind.

Paleoindian groups from earlier times had constructed retaining walls of piled rock and brush that enhanced the natural contour of the parallel slopes. This continued until the narrow valley culminated in a thousand square foot natural depression in the landscape that would serve as holding pen for the animals. It was here that the herd would be concentrated and harvested. With their freshly sharpened spears and darts, the hunters would be prepared to efficiently kill, clean and process their catch.