I.

Ni was a strong and wise Paleoindian woman. At barely five feet tall she was of typical small size for her people, but her spirit bounded high above the trees. Ni was a matriarch. At roughly thirty-five years old, she was one of the few “elders” among her group. At this age her power and influence were at their peak. She was beloved by and devoted to the sixteen other individuals in her band. Nine of them were her direct descendants. The remainder had joined the group over the years and had become her family too.

Throughout the year, Ni’s close-knit group would rotate their residence between long established camps. They were an opportunistic people. They traveled extensively and followed the path of the great river as it coursed through their native lands. As they moved, they would optimize their resources along the way. They hunted local and migratory game and foraged the ever-changing vegetation. Each summer they would move East toward the edge of the forest as it approached the expansive coastal plain. When winter approached they would retreat inland to familiar and safe habitat among the rocky hills and protected forest.

There were many other similar extended family groups in the region. Most maintained peaceful relationships with one another and would congregate throughout the year. When bands came together in the summer months, they would meet at one of several strategically located coastal camps. Despite several local encampments vying for similar resources, peaceful relationships were generally maintained throughout the years. Warfare was uncommon, and typically one sided and dramatic when it did occur.

During the annual summer encampments, the energy and collective activity of the people surged. From these loci they would set out in communal game drives, fish runs, and in collection of ripening wild edible plants until their abundance was gone. These camps were also an important place for socialization. They were places for feasting, exchanging information, finding mates, renewing kinship bonds, and performing ritual activities. They were transformational sites, where animal and other organic products were made into food, clothing, tools, and other assorted necessities of their ancient lives. The seasonal gatherings provided these ancient people opportunities for learning new skills and for the refining of the old ways. These camps also provided opportunity for the older individuals to impart their knowledge upon the young. One such of these summer camps was called Siwaba.

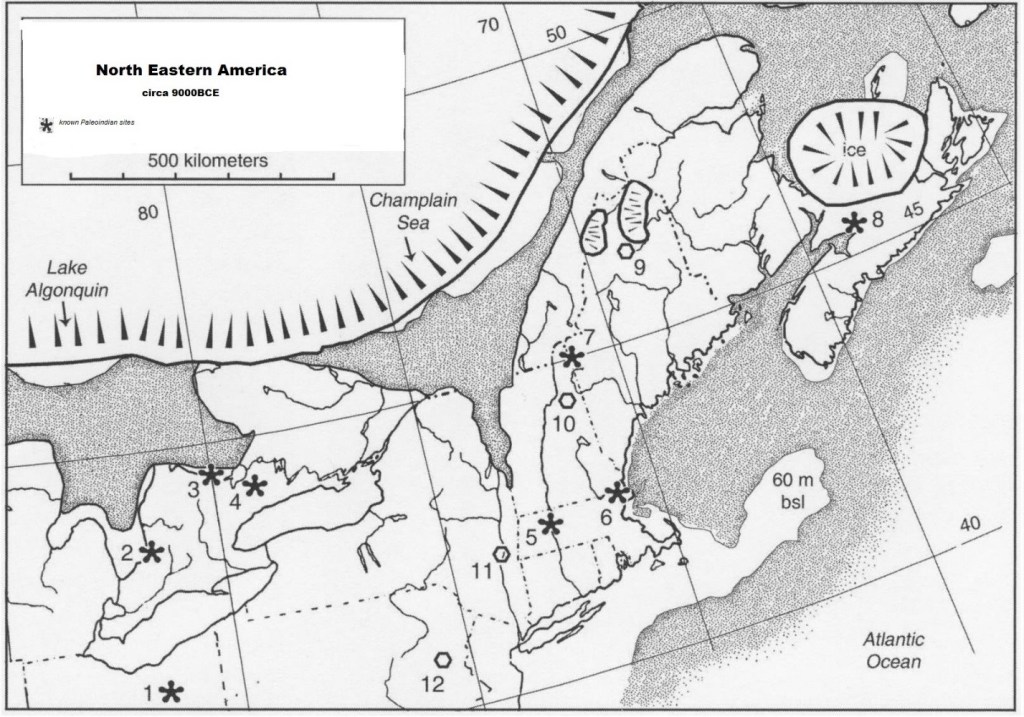

Each year as the spring temperatures began to rise, Ni’s clan would anticipate their annual trek to Siwaba, her ancestral camp. It was there that multiple families would come together as the flowers bloomed, grasses greened, and the caribou embarked on their southern migration. Typically, four or five bands representing roughly fifty to sixty individuals would be expected to congregate. Excitement would fill the air as preparations were made for the long hike down river. Stone and tools were gathered, food was packed, and children were bundled. Siwaba was a place that Ni was particularly fond of, and it was where she felt the most content. It was here that she first encountered the ocean when she was a child. It was here that she had given birth to several of her offspring. It was here that she would ultimately die. Ni and her people inhabited the area that is present day New England in the early Holocene epoch – around 8500 BCE. They were descendants of the nomadic hunter-gatherers who first populated North America.

It is believed that around 12,000 BCE ancient people moved into modern day New England following the retreat of the Wisconsin Glacier. They moved across the continent hunting large migratory mammals like mastodons, caribou, bison, and mammoths. They traveled Eastward, across the northern plains, below the Great Lakes, through the Ohio Valley, through New York, and onward. Along the way, they sheltered in caves and built crude shelters from brush and hides. Exploring the unknown terrain, these early pioneers had to adapt quickly to unfamiliar environments. Their survival hinged on collective experience and relied heavily on their developing innovation and ingenuity.

After initial habitation of the Northeast, there was a long period of global cooling (Younger Dryas period ~ 11,00BC-9,500BC). At this point in time, the local climate system was uniquely sensitive to rapid changes due to the proximity of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and the North Atlantic Ocean. The changing environment presented new and unique challenges for Ni’s predecessors. As the human population and its pressure to survive increased, so did the need for cooperation on a large scale. Social banding developed and became a necessity to ensure survival and proliferation.

These early Paleoindians began to look for alternative ways to sustain life without moving large distances. Part of their focus became staking out territory and negotiating relationships with nearby communities. Due to the constraints of available natural resources, early communities were not very large, but they included enough members to facilitate some degree of division of labor, security, and reproduction. It was in this developing habitation model that agricultural societies began to form, and from which the Neolithic Revolution would eventually emerge. The beginnings of organized religion would also soon emerge and evolve globally.

In ancient New England, as the glaciers continued their Northward retreat, new lands that once laid hidden were slowly revealed. The deglaciated landscape appeared as rounded hills, wide valleys, numerous lakes and bogs, thin soils of clay, silt, sand, and an abundance of stones and boulders. Open woodlands would eventually develop, followed by forests of birch, spruce, and pine. Newly observed species of various fish, plants, birds, and small game flourished and began to provide for the new comers. The geographic boundaries of this maritime peninsula were further defined by the St. Lawrence River and the coastal plain. This plain served as great highway and afforded periodic infusion of new ideas and new people.

The Paleoindians of Ni’s time were similar in capacity to modern humans. Their language was relatively basic though effective. Given the circumstances of the time they had not required nor developed extensive vocabularies, nor the ability to read or write in the modern sense. They dedicated their cognitive and psychosocial abilities to what was necessary – survival. They relied much more on their senses than we do today. They had a keen ability to observe and understand another’s body language or facial expressions. They had awareness of the movement of grasses and animals, weather patterns, the movement of the moon, stars, and the sun. With ease, they could identify potential threats around them – like hearing an unfamiliar footstep or vocalization, tasting a poisonous or spoiled food, and smelling the presence of others. This allowed them to steer clear of danger, navigate, and hunt safely and effectively.

Despite their limited vocabulary, storytelling was an integral part of the culture. Circled around a fire, Ni would connect deeply with her band by passing on stories that were expressed to her in similar tradition. It was in the experience of sharing these stories that strong relationships developed within her group, encouraged their creativity, and the most important life lessons were taught. Often her stories would detail the movement of things they observed, for it was the environment around them that provided the basis for their learning. Animals, people, the river, the grasses, the trees, the seasons, and the weather were all common characters in her stories as she tried to explain the eternal flow of life and death that they would all eventually experience. Mateg and Awaas were two individuals who would always sit the closest, listening and watching Ni intently.

In their mid-teenage years, brothers Mateg and Awaas were physically developing into men, though remained childlike in their play and affection. The two had become critical to the survival of their group as they were also skilled hunters, artisans, and foragers. They were perfecting their flint knapping skills, and soon they would begin to sire children of their own. Mateg was the older of the two, though he appeared remarkably smaller and more reserved. Like Ni, he had a knack for leading rituals and had a natural ability to calm the anxieties of those in his group. Awaas was a large, hirsute, and boisterous man-child that often drew the ire of the group elders for his exploits. He often was the source of quarrels, and his brother Mateg would typically be the one to mediate some resolution. Ni loved them both entirely. She had raised them both as her own. The brothers had become orphans at an early age when their mother died following childbirth with Awaas.